Sizing up achievement even when it feels like a drop in the ocean: a climate equity example

by Suhlle Ahn

Just how the balance of power gets tipped can feel like a mysterious thing, even though there are some consistent statistical patterns behind this.

Power and entrenchment of status quo interests can be intractable… until they’re not.

Change seems to stall and stall and stall until suddenly the floodgates open, often to the surprise of everyone.

Credit: AP News

COP27: Glass half-full, or half-empty?

A week out from the wrap-up of COP27 in Sharm el-Sheik, Egypt, the general consensus on the final agreement seems to be this: it’s kind of a glass-half-empty, glass-half-full verdict.

And how you measure “success” or “failure” may depend on whose perspective you take.

…which, it occurs to me, can be a lot like measuring the gains of equity work in general.

But not to get ahead of our skis…

Let’s first review why the glass looks half-empty and half-full:

On the one hand, the final deal—and the conference overall—was marred by the failure of the parties (COP stands for Conference of the Parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, or UNFCCC) to reach a unified commitment to phase out—not just “phase down”—fossil fuels.

In short, it punts on taking collective responsibility to address the ROOT CAUSE of climate change: carbon emissions. And ultimately, our only hope of averting catastrophic environmental consequences lies with our ability, collectively, to keep global temperatures below 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. This in turn depends on our ability to cut carbon emissions quickly enough, which in turn depends on our ability to phase out fossil fuel use.

On the other hand, the agreement to create a loss and damage fund (LDF)—which (if properly followed through on) will help countries most vulnerable to climate-related disasters rebuild—represented a historic breakthrough and was seen as a major win for civil society groups, as well as the many small island nations and less-industrialized countries least responsible for, yet inequitably harmed by, the consequences of global warming.

Head of Greenpeace Southeast Asia and climate activist Yeb Saño called the breakthrough a “new dawn for climate justice” and a “victory for people power.”

To sum things up, Michael E. Mann may have put it best when he wrote:

“we must be able to wrap our minds around two seemingly opposing realities: We are making substantial progress, and yet it’s wholly insufficient to the scale of the challenge.”

*

When the fine print really matters

As many have pointed out, the omission of the words phase out instead of phase down largely reflects the outsized power and influence of the oil and gas lobby at COP27, which actually saw a 25% increase in attendance this year over last.**

As CEO of the European Climate Foundation, Laurence Tubiana, put it,

“The fossil lobby’s fingerprints are everywhere in the agreement as they battle the inescapable phase-out of their billion $ subsidies.

This term, "phase out", failed to make the final text.

We all have a target for next year.”

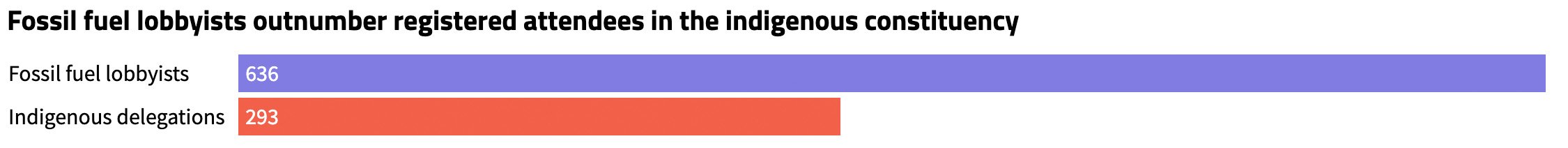

Whose voices are the loudest?

For a visual snapshot, here’s how those lobbyist numbers stacked up against the numbers of attendees from the largest African and Indigenous delegations:

A year ago, we did a post-mortem on COP26, quoting the stirring words of Prime Minister of Barbados Mia Amor Mottley about the need for “the correct mix of voices, ambition, and action” to solve the climate crisis—a mix clearly not achieved a year later.

But the fossil lobby backstory shows that it’s even worse—that the absence of a correct mix of voices FOR DECADES now has been no accident.

Not only did the oil and gas lobby have its fingerprints all over this year’s agreement, it’s had its fingerprints on every agreement since the establishment of the UNFCCC at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992.

Even well before that—from the earliest days of the environmental movement in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s—fossil fuel (and chemical) industry interests had begun work to shape the public conversation, via the new field of “public relations” and PR men like E. Bruce Harrison, sometimes referred to as the “godfather of greenwashing.”

(Listen to this episode of the podcast “Drilled” by climate journalist Amy Westervelt to learn more.)

*

The making of systemic inequality: a case study

If you’ve ever felt fuzzy about the meaning of the term SYSTEMIC, the example of E. Bruce Harrison and his role in shaping the agenda at COP may help shed some light.

It shows how history and the cumulative effects of time always play a part in how systems evolve and materialize, and how inequities can result, whether or not the consequence of a deliberate strategy by an individual decision-maker, as was the case with E. Bruce Harrison.

According to Westervelt, as the push for environmental regulations grew stronger through the ‘70s and early ‘80s, Harrison

“brought auto makers, manufacturers, utilities, oil, gas, and coal companies together to figure out a strategy. He called it The Global Climate Coalition. And the first thing he did was get its members into the international climate meetings of scientists and politicians that were just starting. GCC members, and Harrison himself, were involved in shaping the UN Framework on Climate Change. They were there weighing in on the very first report from global climate scientists, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report in 1992. They were at the very first international climate conference, the Rio Earth Summit, pushing world leaders to embrace the idea that there was plenty of time to act on climate change, that we shouldn’t risk economic hardship to do it, and that in fact business could be trusted to do this work voluntarily.”

Westervelt goes on to say,

“In the 1980s and 90s [Harrison] worked on behalf of oil, automotive and manufacturing clients to push the idea that industry was already working to combat the greenhouse effect and could be trusted to manage emissions and any necessary energy transition themselves.”

These industry voices, in short, have been at the decision-making table from day one, often counted among national delegation members or non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

Whose voices have been kept quiet?

And whose voices have not been at the table? Or have had much less weight, when present?

Generally-speaking, it’s been the Global South, the small island nations, and the least industrialized countries of the world. (For a look at the Global North-South divide and some of the climate issues involved, read here.)

That COP27 was called the first African COP is no minor milestone.

And it may help to remember that, despite its mandate to act on behalf of ALL nations and ALL mankind, the UN itself was formed by the Allied Powers after WWII, all of which are permanent members and have veto power. At the time of the UN’s founding in 1945, much of Africa and Asia were still under colonial rule.

LDF: example of a significant equity measure

It’s within THIS context that we have to understand the monumental nature of the loss and damage fund as a major equity advance, especially coming after some dramatic gridlock that sent COP negotiations into overtime—with the US, as the last hold-out, finally relenting.

But to also understand the significance of what the LDF inclusion COULD mean moving forward, it’s worth listening to this speech—once again by the peerless Mia Mottley—given just ahead of COP27.

In it, she explains the Bridgetown Initiative, or Bridgetown Agenda, which really should be understood in lockstep with the loss and damage fund, as a set of international finance reform proposals to help finance loss and damage and other climate adaptation costs already falling disproportionately to countries least responsible for causing the problem. (Skip to 1:02:39 if you can’t commit to the whole speech, but you’ll be missing out!!)

In short, it isn’t just that wealthy nations have agreed (in principle) to pay into a fund, as if it’s an act of charity.

It’s that the rules of financing around climate action are—potentially—about to be re-written; that reforms to some of the most powerful international financial institutions, including the World Bank and the IMF (International Monetary Fund)—whose rules have long tilted in favor of former colonial and imperial powers—are about to be enacted, in such a way that the COP27 loss and damage fund won’t turn out to have been an empty promise.

To invoke the language of Equity Sequence®, you might say that, while the fossil industry still exercised outsized power over the COP agenda, the Bridgetown Agenda (call it your Equity Sequence® “this”) was designed with equity in mind.

As just one example of the existing finance system tilted in favor of Western Europe (and Japan), Mottley reminds us that “standard borrowing costs on international markets are generally around 1-4% in G7 countries but can be as high as 12-14% for much of the Global South.”

Who benefits and who is disadvantaged by THAT?

She likewise calls out two examples of Western European countries that have benefited from historically favorable finance terms: Germany, whose annual debt payments after WWII were capped by Allied creditors in order to allow it to rebuild; and the UK, which was allowed to take out long-term debt to finance its WWI (yes, World War One) spending and only paid off the last of this debt in 2014 because it “could not handle the repayment amid its other spending priorities.”

Yet today—unless a pivot is made toward comparable, more equitable terms to help lower-income countries finance solutions to the present and future crisis they face—they will be forced to “sacrifice their [own economic] development goals for climate spending.”

No matter how you slice it, the objective unfairness of their predicament is staggering.

One more thing to note: the Bridgetown Initiative—part of which calls for “innovative sources” of loss and damage funding—could lead to funding not just from wealthy nations—i.e., governments—but also from private sector polluters, in line with a “polluters pay” principle and movement. This could come in the form of a tax on the fossil fuel industry, for instance.

That Mottley’s Bridgetown Initiative received strong support from two powerful figures, Managing Director of the IMF Kristalina Georgieva and President Macron of France, is telling.

And that the COP27 LDF agreement was secured in tandem with this broader initiative may make it a bigger deal than first meets the eye.

In short, the concession by wealthier nations to commit to the LDF may be the sign of a larger movement of change.

*

At Tidal Equality, we often speak about the need to make decision-making more democratic and participatory. We often speak, too, about the 25% committed minority needed to reach a tipping point that can lead to a shift in societal norms, behaviors, and opinions.

Calls for a more equitable finance landscape—of which a loss and damage fund is one example—have been on the table for 30 years, with less-industrialized, less-wealthy nations pushing for, and the US in particular pushing against.

If the LDF, together with the broader Bridgetown Initiative, become reality; if they can spark, as Mottley clearly wants them to, real change toward a more equitable financial playing field, then we may just be witnessing a tipping point of this magnitude.

Viewed in this light, the significance of the LDF lies in its potential to do what the voices of the many have not been able to do for three decades—namely, start to shift the weight of decision-making power from those historically few nations with outsized power in the UN—including the fossil fuel industry players who have huge influence in those nations—to the many, some of which did not even exist at the time of the UN’s founding.

*

And yet…that glass is still half empty. And we are still too far from what we need to do in the little time we have left to avert planetary collapse.

So what value do we place on this equity win?

How do we even measure progress?

Perhaps one lesson we can draw from COP27 is about what advocating for equitable change writ large—in organizations, and in society—can look and feel like. And why it can sometimes seem meaningful and futile all at once.

Quite simply, it’s a slog.

At Tidal, we talk a lot about bottom-up change and the power of making equitable change one decision at a time. But we are not so naïve as to think that each action in and of itself is sufficient.

Just how the balance of power gets tipped can feel like a mysterious thing, even though there are some consistent statistical patterns behind this.

Power and entrenchment of status quo interests can be intractable…until they’re not.

Change seems to stall and stall and stall until suddenly the floodgates open, often to the surprise of everyone.

And yet even when a major stride forward occurs, it can feel like a drop in the ocean when viewed against the insurmountable size of that ocean.

When it comes to the climate crisis, there IS consensus, scientifically shared, about what constitutes an objective goal: the 1.5°C temperature rise limit.

But it would seem that, with equity work, there’s no such objective, universally-accepted measure.

So it raises the question: who is the arbiter of what constitutes a valid measurement of an equity “win” or “gain”? (Hint: it may require regular pulse-taking with the underserved or disadvantaged parties in question...)

Maybe we have to find ways to measure both.

Maybe we have to recognize that you don’t look at a relatively small win and deceive yourself into thinking you’ve changed the world.

Nor, on the other hand, do you look at a significant win and reduce it to nothing, even if the larger problem can make it seem like weak tea.

You keep going. You see your half-full glass and also see its half-empty twin. And you keep pouring in the hope of pushing that fill line closer and closer to the rim.

Or, to return to some words from Michael E. Mann, on the subject of climate:

“we must fight the notion that it is too late to do anything or buy into the notion that it is time to abandon the only multilateral framework that exists for negotiating international climate action. It is ironically that flawed belief that most threatens meaningful climate progress. The COP process is the worst process in place to achieve these goals—except for all the others.”

And:

“It helps to remember that “every bit of climate progress that we make reduces harm, suffering and damage for us, our children, and our grandchildren.”

In like vein, it may help to remember that every bit of progress we make toward a more just and equitable world, and toward more just and equitable organizations, can reduce harm and suffering for SOMEONE. For another human being. And maybe that is motivation enough.

** It’s not the only factor, though. Last year it was India that pushed for a change from “phase-out” to “phase-down,” and this points to the complicated question of what is fair, not just for under-developed nations but historically “developing” nations like China and India, which have rapidly become huge carbon emitters over the past two decades but were not as of the 90s, when COP was first established.

Suhlle Ahn

VP of Content and Community Relations